- Essential Bookkeeping Habits For Audit Ready Books in Canada

- Canadian Income Tax Compliance

- Canadian Controlled Private Corporations

Canadian Controlled Private Corporations

The Bookkeeper's Notes on CCPC

By L.Kenway BComm CPB Retired

Edited November 16, 2024 | Updated November 15, 2024 | Revised June 28, 2024 | Originally Published on Bookkeeping-Essentials.com in April 2010

NEXT IN THIS SERIES >> How To Review Your T2 Tax Return | Common T2 Schedules

BOOKKEEPER'S HANDY REFERENCE

Caution - Talk to Your Accountant

Please use the information in this section more for talking points with your accountant ... so you have a better feel for what kind of information you are seeking. Your accountant will customize advice specifically for your situation. Think of it like this ... Having a map BEFORE you enter the forest is so much better than getting lost in the forest!

I'm going to be upfront here. I do not have a lot of experience with CCPCs (Canadian controlled private corporations) as I specialized in sole proprietorships so this page is just The Bookkeeper's Notes on CCPCs.

This is where I tracked things as I learned them so I can have easy reference back to them later.

Canadian controlled private corporations have unique tax planning opportunities in Canada, especially for the owner managed corporations.

I found there is a wealth of free information on self-employment and/or sole proprietor bookkeeping and taxes ... but not so much on how to keep corporate books or how to prepare your corporate tax return. I'm guessing it is because it is a more complex subject and a mistake could cost you a lot of money such as:

- not making an election when needed, or

- utilizing owner manager remuneration strategies incorrectly, or

- not planning in advance how you are going to use your capital losses before they expire (note to self- do they even expire now?)

It is very hard and expensive for an accountant to get you out of hot water once you're in it. Some things can't be fixed, so what's done is done. You pay for your mistakes - an expensive lesson on learning the CCPC rules.

So PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE check with your accountant before you implement any topics I mention here because they really are just The Bookkeeper's Notes on Canadian controlled private corporations and I may not fully under the nuanced complexities pertaining to many corporate taxation issues.

Highlights Of This Post

- What is a Canadian controlled private corporation (CCPC)?

- Is Incorporating Right For Your Business?

- What is the Business Corporations Act?

- Types of Tax Payable for Canadian Controlled Private Corporations

- What is the SBD?

- Tax Rates and Thresholds for Corporations (Small Business Deduction - SBD)

- Small Business Rate Reduction Restrictions (includes taxable capital employed and taxable capital business limit reduction)

- How the CCPC and SBD Rates are Calculated

- Active Business Income - Schedule 7

- Passive Investment Income Rules

- Corporate WCB Owner Obligations and Services - Employers' Advisors Office

- Selling or Redeeming CCPC Shares

- What is the LCGE?

- Inactive Corporations

FAQ Canadian Controlled Private Corporations - Taxing Passive and Investment Income

- What is subsection 20(12) deduction of the ITA? Income tax withholdings of foreign income

- What is the main purpose of Refundable Part IV Tax? What are sections 112, 113, 138(6) of the ITA referred to when preparing Schedule 3 of your T2?

- What is the RDTOH and how does it work?

- What is the capital dividend account in Canadian controlled private corporations?

- I want to pay a capital dividend. How do I do this? Where do you find your CDA (Capital Dividend Account) balance and how you confirm this balance with CRA?

- What is the difference between passive income and SBI?

- What is the difference between specified corporate income (SCI) and specified investment business income (SBI)?

- Is specified corporate income the same as income splitting or income sprinkling?

Other Information on Canadian controlled private corporations

- Tax Compliance Notes for Corporations (opens to a different page)

- Director's Liabilty for Taxes (opens to a different page)

- T2 Tax Payable Part 1 Calculation (opens to a different page)

Incorporated Tax Compliance

Learning The Rules

Owner-Manager Compensation ... Coming Soon

Owner-Manager Compensation ... Coming Soon

What is a CCPC?

To be a Canadian Controlled Private Corporation (CCPC) you must meet the following criteria:

- The corporation must be a resident of Canada; incorporated in Canada or a resident from June 18, 1971

- It must not be controlled by one or more non-residents, one or more public companies or a combination of non-residents and public company.

When Should You Incorporate as a CCPC in Canada?

You operate a business as a sole proprietor or a partnership. Is it the right time to incorporate your business as a Canadian controlled private corporation? It's important to understand that incorporation isn't right for every business.

More >> Is Incorporating Right For YOUR Business?

What is the Business Corporations Act?

The Canada Business Corporation Act (CBCA) or their provincial counterparts establishes a particular set of requirements that must be included in corporate minute books among other things.

More >> A table of the Corporation Acts for Canada and its Provinces / Territories

Types of Canadian Controlled Private Corporations Tax Payable

- Part I - Basic rate for "regular" corporate income is 38% of taxable income, 28% after federal tax abatement

- Part II.2 - Tax payable on repurchases of equity (proposed)

- Part IV - Tax on dividends received by private corporations in Canada, particularly Canadian controlled private corporations (CCPCs), from taxable Canadian corporations. More >> Main purpose of Part IV tax

- Part VI - It doesn't apply to Canadian controlled private corporations.

- Part VI.1 - Tax on corporations paying dividends on taxable preferred shares

- Part VI.2 - It doesn't apply to Canadian controlled private corporations.

- Part XIII - Non-residents with Canadian sourced income is subject to a withholding tax generally set at 25%. See below for more on this tax.

- Part XIV - applies to non-resident corporations

More on Part XIII Withholding Tax

Part XIII income tax is a withholding tax in Canada that applies to certain types of income paid or credited by Canadian residents to non-residents. This tax is designed to collect revenue from non-residents who earn income from Canadian sources but do not file regular Canadian tax returns.

Key points to understand about Part XIII income tax and its impact on non-resident corporations:

1. Non-Resident Corporations: For non-resident corporations, Part XIII tax ensures that Canada collects tax on the income earned from Canadian sources. Without this withholding mechanism, these earnings might escape Canadian taxation as non-resident corporations typically do not file regular income tax returns in Canada.

2. Types of Income Subject to Part XIII Tax include passive income such as:

- Dividends

- Royalties

- Rents

- Certain interest payments

- Pension payments including OAS pensions and CPP /QPP benefits

- Management fees

- Estate or trust income

3. Withholding Tax Rate: The default withholding tax rate under Part XIII is 25%. However, this rate can be reduced by tax treaties between Canada and other countries, depending on the type of income and the non-resident's country of residence.

4. Withholding Responsibility: The Canadian payer of these types of income is responsible for withholding the appropriate Part XIII tax and remitting it to the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA).

- AUDIT READY

Miller Thomson's February 8, 2024 article Part XIII Tax – The importance of verifying your landlord’s tax residency states due to a recent court ruling, "Canadian tenants making payments to non-resident landlords are obligated to withhold 25% of the gross amount and remit it to the CRA ... To navigate this landscape effectively, tenants should proactively request a Certificate of Residency from the landlord."

5. Reporting and Remittance: The Canadian payer must report the Part XIII income and the withheld tax on forms such as the NR4 Summary and NR4 Slips, which must be filed with the CRA. The tax must be remitted by the 15th of the month following the month in which the payment was made.

6. Relief under Tax Treaties: Non-resident corporations can benefit from reduced withholding tax rates if a tax treaty exists between Canada and their country of residence. To take advantage of treaty benefits, non-resident entities may need to provide certain documentation, such as a Certificate of Residency from their home country.

TIP

The CRA has an online non-resident tax calculator to help you determine your Part XIII tax liability.

What is the Small Business Deduction (SBD)?

What is the Small Business Deduction (SBD)?

What is the Small Business Deduction (SBD)?The Small Business Deduction (SBD) is a tax incentive available to Canadian controlled private corporations (CCPCs), which reduces their corporate income tax rate on qualifying active business income. The main purpose of the SBD is to support small businesses by allowing them to retain more of their earnings, thereby providing additional funds for growth and investment.

The key points of the Small Business Deduction are:

- Eligibility: To qualify for the SBD, a corporation must be a Canadian controlled private corporation. A CCPC is a private corporation that is resident in Canada and not controlled, directly or indirectly, by non-residents or public corporations.

- Deduction Limit: The deduction applies to active business income up to a certain limit, known as the "business limit". As of recent updates, the federal business limit is $500,000, although provinces and territories have their own limits that can vary.

- Lower Tax Rate: The SBD allows qualifying Canadian controlled private corporations to benefit from a reduced federal corporate tax rate on the eligible portion of their income. The combined federal and provincial/territorial tax rates can also vary, but the resulting rate is significantly lower than the general corporate income tax rate.

- Phase-out Mechanism: The business limit may be reduced for larger CCPCs based on certain criteria, such as the corporation's taxable capital employed in Canada exceeding certain thresholds. The deduction may gradually phase out as the taxable capital increases beyond these thresholds. Adjusted aggregate investment income (AAII) also has threshold limits that affect the SBD deduction.

- Sprinkling and Specified Corporate Income: The rules around income sprinkling (or income splitting) and specified corporate income can also affect eligibility for the SBD. Specified corporate income refers to income earned by a corporation from services or property provided to another private corporation where there is a significant relationship or common control between the two corporations and shareholders.

It's important for business owners to plan carefully, with the assistance of a CPA in public practice, to ensure they meet all eligibility criteria to take advantage of the SBD.

CCPC Tax Rate and Limits - Small Business Deduction

Canadian controlled private corporations are taxed favorably (interpret that as lower or at a reduced rate) on Active Business Income (ABI) up to the small business threshold or limit which was:

- $500,000 federally for 2009 to 2024

- $400,000 federally for 2007 to 2008

- $300,000 federally for 2005 to 2006

- $250,000 federally for 2004

- $225,000 federally for 2003

- $200,000 federally for 2002

This favorable rate reduction is called the Small Business Deduction (SBD).

Small Business Deduction Rates Up To Business Threshold Limit

Amounts eligible for reduced tax rate instead of the general 15% tax rate:

- 2019 to 2024 - 9% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 15%; investment income 38.7%

- 2018 - 10% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 15%; investment income 38.7%

- 2016 & 2017 - 10.5% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 15%; investment income 38.7%

- 2014 to 2015 - 11% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 15%; investment income 34.7%

- 2012 to 2013 - 11% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 15%

- 2011 - 11% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 16.5%

- 2010 - 11% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 18%

- 2009 - 11% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 19%

- 2008 - 11% SBD tax rate; general tax rate 19.5%

Small Business Rate Reduction Restrictions

1. If your CCPC is part of a group of companies, the small business deduction is shared within the group.

2. The Small Business Deduction (SBD) investment limit restrictions refer to rules that limit the eligibility for the SBD based on a corporation's passive investment income. These rules were introduced in 2018 (effective in 2019) to limit access to the SBD for Canadian controlled private corporations (CCPCs) that accumulate significant passive investment income.

More >> Passive Investment Income Rules

3. CCPCs do not qualify for the small business rate reduction if the taxable capital employed in Canada falls within is certain limits. This is referred to as the taxable capital business limit reduction. This mechanism is designed to gradually phase out the benefits of the SBD for larger corporations. When a Canadian controlled private corporation's taxable capital employed in Canada exceeds $10 million, its access to the full business limit begins to reduce.

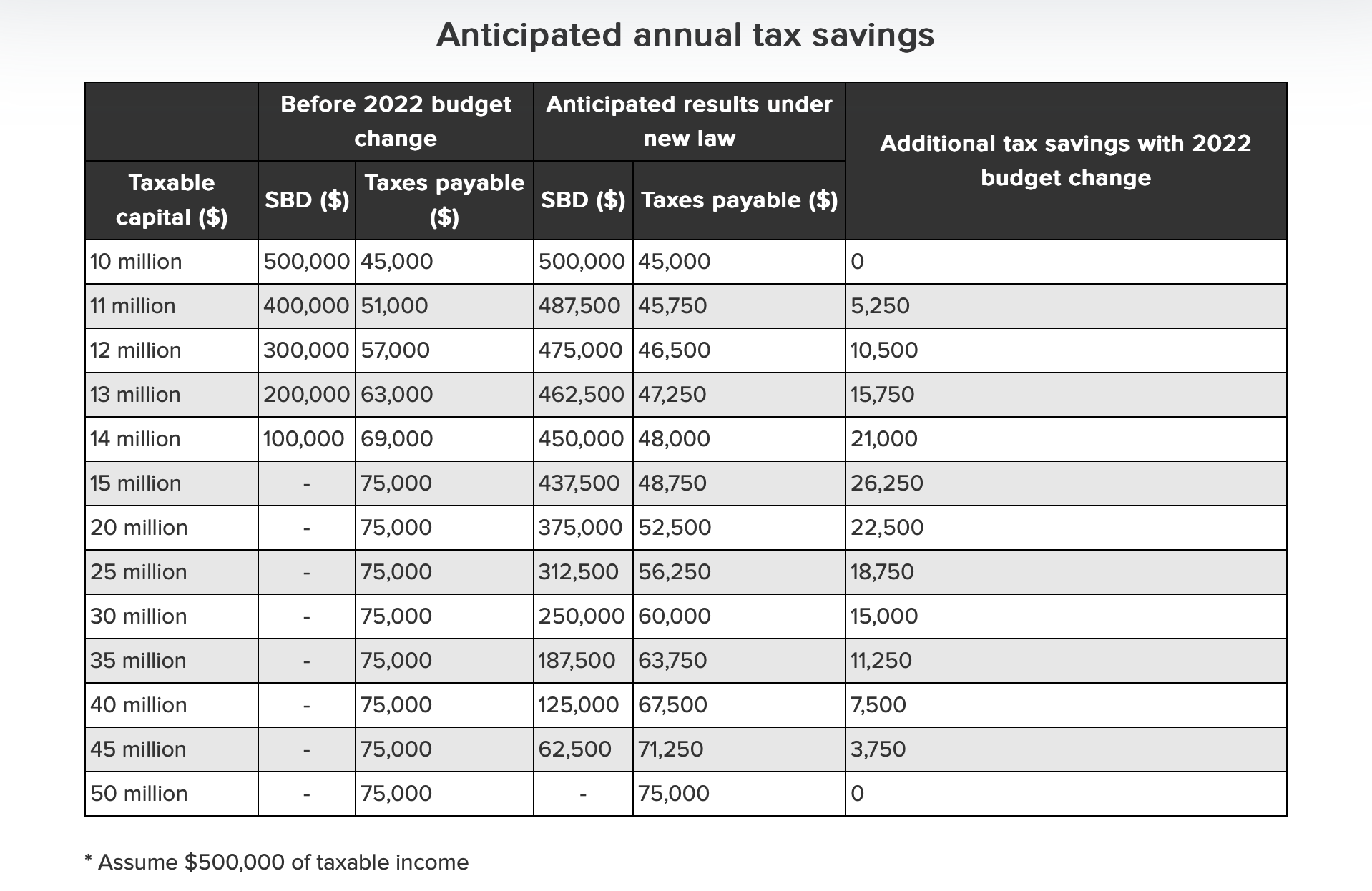

The CRA 2023 T2 Income Tax Guide states: "The business limit is reduced on a straight-line basis for CCPCs that have taxable capital employed in Canada of between $10 million and $50 million in the previous year. For tax years starting before April 7, 2022, the range is $10 million to $15 million." See the chart below for the effect of this change.

This phased reduction is intended to ensure that the SBD primarily benefits smaller corporations, as larger corporations generally have more access to capital and other resources. It’s important for CCPCs approaching or exceeding these thresholds to plan accordingly, as the change in tax rate can significantly impact tax liabilities. It is prudent to discuss this situation with your accountant so s/he can plot a course to optimize your tax strategies.

Taxable capital employed is generally the sum of shareholder equity, loans and advances made to the corporation, surpluses and reserves minus some types of investments in other corporations. It is typically calculated as of the end of the previous tax year. It is an indication of the size of the corporation's operations within Canada.

4. The CRA website explains the reduction in the CCPC business limit will be the greater of (a) its taxable capital business limit reduction and (b) its passive income business limit reduction for the year.

5. CCPCs receive a break on their filing deadline if they don't have passive income.

CCPC Tax Rates

Find 2008 to 2024 Canadian controlled private corporation tax rates and business limits for all provinces and territories by clicking here. Clicking on the link will open a separate window that takes you to my favorite tax site. Remember to come back here when you've found what you needed.

How the CCPC tax rate vs SBD tax rate is calculated:

|

A. After the general tax reduction, the net tax rate is 15% calculated as follows: General corporate tax rate 38% |

B. After claiming SBD, the net tax rate is 9% calculated as follows: General corporate tax rate 38% |

*Personal Service Corporations do not qualify for this rate. They are taxed at 28% (the general corporate rate less the federal abatement). There is an additional tax on investment income. Provincial corporate tax is an additional tax. Effective January 1, 2019 new passive investment income rules also affects the small business deduction.

Active Business Income (ABI) and Specified Investment Business Income (SBI)

What is active business income (ABI)? ABI defined under ITA 125(7). It is any income of a corporation other than income from property, a specified investment business, or a personal services business. The income is generally earned through the day-to-day running of the business.

Incidental income on surplus funds may still be included in ABI; that is interest from temporary cash balances or temporary rentals of excess space. Long term investment holdings may not be included in ABI as generally it is not intended to support the day-to-day running of the business.

For ABI to qualify for the SBD, the income must be earned in Canada.

Schedule 7 in the T2 tax return calculates ABI which excludes:

- Passive income such as investment income which includes taxable capital gains net of allowable capital losses, property income net of property losses, and foreign business income. As mentioned, incidental property income is deemed ABI.

- The concept of a substantive CCPC was introduced in the 2022 federal budget. It targets tax planning strategies implemented to restrict a Canadian controlled private corporation from artificially losing its CCPC status by manipulating a corporation's status to defer tax on passive investment income. Grant Thornton explains it like this, "In other words, under the new rules, a corporation would be considered a substantive CCPC if the only reason it isn’t a CCPC is because a non-resident or public corporation has the right to acquire its shares."

- Specified Investment Business Income (SBI) whose main purpose is to earn income from property such as interest, rent, royalties or dividends income. There is an exception if you have five full-time employees working on this.

- Personal Service Business (PSB) income from an incorporated employee. There is an exception if the PSB has more than five full time employees.

- If you have no passive income, you do not have to complete this schedule when preparing your T2 corporate income tax return.

Passive Investment Income Rules

Effective January 1, 2019, new passive investment income rules came into effect that may clawback your Small Business Deduction. Canadian controlled private corporations can earn between $50,000 and $150,00 in passive income before the business limit phases out. Previously the phase out was only based on taxable capital employed in Canada.

Here are the key aspects of the SBD investment limit restrictions:

1. Investment Income Threshold: The rules come into effect when a CCPC and its associated corporations earn more than $50,000 in aggregate annual adjusted aggregate investment income (AAII) in the previous fiscal year. AAII includes income from investments such as interest, dividends, royalties, and capital gains, with some adjustments for tax purposes.

2. Reduction of Business Limit: If the CCPC's AAII exceeds $50,000 in the previous fiscal year, the business limit is reduced and eventually phased out. Specifically, for every $1 of AAII above $50,000, the business limit is reduced by $5.

3. Complete Phase-Out: The business limit is fully eliminated when the CCPC's AAII reaches $150,000. This means that CCPCs cannot claim the small business tax rate on their active business income once their AAII hits this threshold.

4. Interaction with Taxable Capital Limit: The smaller of the two reductions (from taxable capital and investment income) applies to the business limit. This means both the taxable capital employed in Canada and AAII can separately or jointly affect the SBD eligibility.

These restrictions are intended to ensure that the small business deduction benefits small- and medium-sized active businesses that reinvest their profits into growth, rather than those benefiting primarily from investment income. For corporations that are closely approaching these thresholds, careful tax planning with assistance from a CPA may be necessary to manage these limits effectively.

More >> Taxing Passive Investment Income

WCB Owner Obligations and Services

If your BC CCPC has employees (even if it is just you) you must report the salaries / wages to WCB and pay assessment premiums as per section 38 and 39 of the WC Act.

You are exempt from registering with WCB if your CCPC is classified as a personal financial holding company whose activities and income are passive. The criteria includes:

- The only workers are shareholders of the corporation.

- The company invests only its own assets and/or the assets of its principals.

- No activities are pursued except the shareholders' own personal financial investments like publicly traded stocks and bonds, interest bearing instruments and non-revenue producing land, buildings or equipment (i.e. no rental activity).

More >> WCB tax filing deadlines

B.C. Employers' Advisers Office

Please note - these services are available to sole proprietor and partnerships as well as corporations.

The experts at Employers' Advisers work independent of WorkSafeBC under section 94(3) of Worker's Compensation (WC) Act. They can help you manage your compensation costs to give your business a competitive advantage.

There is no charge to use their services because the cost of their offices are included in assessments.

They provide assistance, education, advice and representation to employers on WorkSafeBC issues.

Compliance with the WC Act is mandatory. While ignorance of the law is not a defense, due diligence is. This requires everything to be in writing otherwise your due diligence does not exist.

Two forms you want to ensure are complete are Due Diligence Checklist and New Worker / Young Worker Orientation Checklist. Both can be found on the www2.gov.bc.ca website.

WorkSafeBC SURCHARGES TIP

If your tax compliance rates include a surcharge, you need to do something to reduce it back to the industry average.

The surcharge you pay is based on your claims rate which can be 100% higher than the industry average. It is a weighted average over a three year period. Call an employer advisor to provide advice on how to lower your premiums.

An excellent reference is Health and Safety for Small Businesses: A Guide to WorkSafeBC. It is available on the worksafebc.com website.

Alberta also has an Advisor Office for Alberta Worker's Compensation (advisoroffice.alberta.ca) as I'm sure other provinces would as well.

Selling or Redeeming CCPC Shares

CCPCs have two different tax treatments for selling shares and redeeming shares.

CCPCs have two different tax treatments for selling shares and redeeming shares.Canadian controlled private corporations have two different tax treatments for selling shares and redeeming shares.

- Sale of shares to third parties are subject to capital gains. Capital gains are eligible for the lifetime capital gains exemption (LCGE) which means sale of the CCPC shares could have no tax consequences.

- Redemption of CCPC shares are subject to a deemed dividend (ineligible) which is taxed at your marginal tax rate. Any taxable capital loss may qualify for an allowable business investment loss (ABIL). This transaction does have consequences.

An arms length sale of the CCPC shares would avoid the deemed dividend.

Learn more about these options at wrightbusinesslaw.ca> share-sale-or-corporate-redemption.

What is the Lifetime Capital Gains Exemption (LCGE)?

The Lifetime Capital Gains Exemption (LCGE) is a provision in the Canadian tax system that allows individuals to realize tax-free capital gains up to a certain limit on the sale of qualifying properties. This exemption is designed to encourage investment in small businesses, farming, and fishing by offering tax relief on gains from these investments. Here are the key details of the LCGE:

1. Eligible Property: The exemption typically applies to capital gains on the disposition of:

- Qualified small business corporation shares (QSBCS).

- Qualified farm property.

- Qualified fishing property.

2. Exemption Limit: As of 2024, the cumulative lifetime exemption limit is $1,016,836* for qualified small business corporation shares. This amount is indexed to inflation and may change annually. As of 2024**, the limit for qualified farm and fishing property is no longer separate.

Maximum capital gains exemption (CGE) where capital gains deduction is 50% of exemption.

| Disposition Year | LCGE | Farming Fishing |

|---|---|---|

| 2026* | indexation resumes | indexation resumes |

| After June 24, 2024 - Dec 31,2025* | $1,250,000 | $1,250,000 |

| Before June 24, 2024 | $1,016,836 | $1,016,836 |

| 2023 | $971,190 | $1,000,000 |

| 2022 | $913,630 | $1,000,000 |

| 2021 | $892,218 | $1,000,000 |

| 2020 | $883,384 | $1,000,000 |

| 2019 | $866,912 | $1,000,000 |

| 2018 | $848,252 | $1,000,000 |

| 2017 | $835,716 | $1,000,000 |

| 2016 | $824,176 | $1,000,000 |

| After April 21, 2015** | $813,600 | $1,000,000 |

| Before April 21, 2015 | $813,600 | $813,600 |

| 2014 | $800,000 | $800,000 |

| 2008 - 2013 | $750,000 | $750,000 |

LCGE Maximum Notes:

* CPA Canada News October 15, 2024 article Taxpayers in limbo: Compliance in uncertain times says "The legislation to enact these proposed [2024 Federal Budget] changes has not yet been introduced in the House of Commons, and with the minority government stuck debating parliamentary privilege and facing multiple non-confidence motions, it is hard to determine when, or even if, these tax proposals will reach royal assent.".

** In 2015, significant changes were made to the LCGE. These changes were part of broader measures aimed at supporting small businesses, farms, and fisheries, encouraging investment, and reflecting inflationary realities over time.

- Increase in the Exemption Limit: The federal government increased the LCGE limit for qualified qualified farming and fishing properties to the greater of $1,000,000 and the indexed LCGE for QSBCS. This change was a significant boost from the previous limit, allowing certain individuals to shelter more of their capital gains from taxation.

- Indexation to Inflation: Starting in 2015, the LCGE amount became indexed to inflation. While the specific exemption amount was set at $1,000,000 for qualified farm or fishing properties, indexing aimed to ensure that the exemption amount for small business corporation shares would adjust over time, potentially affecting future limits. Once the QSBCS exceeded $1 million, the LCGE would be the same for everyone. This occurred in 2024.

3. Requirements for QSBCS: To qualify as QSBCS, certain criteria must be met, including:

- The shares must be of a small business corporation, which is a Canadian-controlled private corporation (CCPC).

- The business must use at least 90% of its assets in active business pursuits in Canada at the time of sale.

- The shares must generally have been held for at least 24 months prior to disposition.

4. Family Transfers: The LCGE can also be beneficial in family business succession planning, as it may apply to the transfer of ownership from one family member to another.

5. Use of Exemption: The exemption is lifetime, meaning you can only use the exemption amount available to you once and it is reduced by any amounts you have used in previous years.

6. Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT): While LCGE allows for tax-free capital gains, individuals should be aware that claiming the exemption may trigger the Alternative Minimum Tax in certain situations.

7. Documentation and Compliance: Proper documentation is crucial to support a claim for LCGE. The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) may require evidence that the shares or properties meet all the qualifying conditions.

Learn more about how to take advantage of the LCGE.

Inactive Corporations

Remember, even if you don't owe taxes or your company is inactive, you still have to (as in must, are still required to) file your corporate tax return.

The permanent records of the corporation must be retained two years from dissolution. Mergers and amalgamations are a continuation of the business.

FAQ Canadian Controlled Private Corporations - Taxing Passive and Investment Income

As mentioned when I started this article, completing Canadian controlled private corporations' tax returns is not my forte. You need to know a fair bit about the Income Tax Act (ITA) so you understand your deductions and special elections.

Here are just a few ITA (income tax act) references you might come across when you read your T2 prepared by your accountant if you have passive income.

What is subsection 20(12) deduction of the ITA? Income tax withholdings of foreign income

What is subsection 20(12) deduction of the ITA? Income tax withholdings of foreign income

When preparing your T2 corporate income tax return, you may come across references to subsection 20(12) of the Income Tax Act (ITA) as it pertains to foreign non-business-income taxes paid by a taxpayer.

This section deals with income tax withholdings of foreign income. The deduction under this section allows a tax payer to deduct the foreign tax paid on non-business income such as foreign dividends income, interest income, rental income, or royalty income. Under this paragraph, you have the option to choose to deduct only a portion of the foreign tax paid under subsection 20 (12) or not deduct any.

What is the main purpose of Refundable Part IV Tax? What are sections 112, 113, 138(6) of the ITA referred to when preparing Schedule 3 of your T2?

What is the main purpose of Refundable Part IV Tax? What are sections 112, 113, 138(6) of the ITA referred to when preparing Schedule 3 of your T2?

The main purpose of the refundable Part IV tax calculated on a T2 corporate income tax return in Canada is to address tax integration and prevent tax deferral through the use of private corporations. Specifically, this tax applies to certain dividends received by Canadian controlled private corporations (CCPCs) from other corporations. Let's look at the three principles that affect the Part IV tax.

- Integration Principle: The Canadian tax system aims to ensure that income earned by a corporation and then distributed to shareholders as dividends is not taxed more heavily than if the income were earned directly by an individual. This is known as the integration principle. The refundable Part IV tax helps maintain this balance by ensuring that certain dividends received by a corporation are effectively subject to the same tax burden as if they were received directly by an individual.

- Preventing Tax Deferral: Without this tax, a corporation could accumulate earnings by investing in other corporations and avoid paying tax on dividends until those earnings are distributed to individual shareholders. The refundable Part IV tax addresses this by applying a tax on dividends received from non-connected corporations (those in which the recipient corporation does not have a significant ownership interest). This discourages using corporations to indefinitely defer taxes on passive investment income.

- Refundable Nature: The Part IV tax is refundable from the RDTOH (refundable dividend tax on hand) account when the corporation pays taxable dividends to its shareholders. When the corporation distributes dividends, it effectively passes the tax burden to the individual shareholder, who would then be taxed on that dividend income. This ensures the tax integration and prevents corporations from using their structure to gain a tax advantage over individual investors.

The refundable Part IV tax is calculated on Schedule 3 and carried forward to the T2 jacket on line 712 Part IV tax payable from Schedule 3. Section 186(1) of the ITA lays out the calculation. Capital dividends are not affected under section 186(1) of the ITA.

T2 Schedule 3 - Dividends Received, Taxable Dividends Paid, and Part IV Tax Calculation is used by Canadian controlled private corporations to calculate their dividend deductions under sections 112, 113, and 138(6). On this schedule, corporations report the dividends received and indicate under which section of the ITA the deduction is claimed (e.g., section 112 for dividends from taxable Canadian corporations, section 113 for dividends from foreign affiliates, or section 138(6) for dividends related to insurance corporations).

When completing a T2 Schedule 3, if you received or paid dividends, the tax program usually asks what section of the ITA the dividend pertains to: Section 112, Section 113, or Section 138 (6). Here's what it is referring to:

- Section 112: Dividends from Taxable Canadian Corporations

This section "permits the receiving corporation to deduct from income an amount equal to the dividend for the purpose of computing its taxable income."* The purpose of this section is to prevent the same income from being taxed multiple times within the corporate structure. It provides an inter-corporate dividend deduction, making the dividends received by the corporation non-taxable. Essentially, this means the income is taxed once at the corporate level and not again at the shareholder level

Example Scenario:

Basic Context:

Let’s imagine Corporation X owns shares in Corporation Y, both of which are taxable Canadian corporations.

Dividend Payment:

1. Corporation Y declares and pays a dividend of $500,000 CAD to Corporation X.

2. Corporation X receives these dividends as part of its investment income.

Tax Treatment:

- Under Section 112(1) Corporation X can deduct the amount of dividend received from its taxable income. This deduction ensures that the dividend is not taxed again at Corporation X's level.

Calculation Example:

1. Income Inclusion:

- Corporation X will include $500,000 CAD as income in its financial accounts.

2. Section 112 Deduction:

- Corporation X can claim a deduction for the full amount of the dividend received, which is $500,000 CAD. The effect is that Corporation X's taxable income for this transaction is reduced by the same amount, effectively excluding the dividend from taxable income.

Journal Entries (for understanding):

Let's say Corporation X’s taxable income before considering this dividend was $1,000,000 CAD.

- Before Deduction: Taxable Income: $1,000,000 CAD + $500,000 CAD (dividend) = $1,500,000 CAD

- After Applying Section 112 Deduction: Deduction: $500,000 CAD

- Adjusted Taxable Income: $1,500,000 CAD - $500,000 CAD = $1,000,000 CAD

Thus, Corporation X’s taxable income remains the same, effectively neutralizing the tax impact of the dividend received from Corporation Y.

Summary:

Section 112 allows Canadian corporations to deduct intercorporate dividends from taxable Canadian corporations, thereby preventing double taxation in corporate structures. This is often utilized in corporate groups where parent and subsidiary entities both operate as separate taxable entities but share profits through dividends. It also arises if a corporation has, for example, a retirement investment portfolio (owns arms length shares) in publicly traded Canadian corporations.

- Section 113: Dividends from Foreign Affiliates

Section 113 deals with the deduction of dividends received from foreign affiliates. "Where the corporation has received a dividend from a foreign affiliate, an amount, as calculated under section 113, may be deducted from the corporation's income for the purpose of computing its taxable income."* I understand that to mean companies in Canada that receive dividends from their foreign affiliates can deduct a portion of these dividends from their taxable income. The amount of the deduction is dependent on various factors including the type of surplus from which the dividend is paid (e.g., exempt surplus, taxable surplus, hybrid surplus, pre-acquisition surplus).

More >> Surplus Accounts and Foreign Affiliate Tax Traps

Example Scenario:

Suppose Company C, a Canadian corporation, owns 100% of the shares of Company F, a corporation based in a foreign country. During the fiscal year, Company F pays a dividend to Company C.

To illustrate how Section 113 operates:

1. Dividend Repatriation:

- Company F declares and pays a dividend of $1,000,000 CAD to Company C.

2. Deduction under Section 113:

- Under subsection 113(1), Canadian corporations can deduct in computing their taxable income an amount equal to certain dividends received from a foreign affiliate. The specific subsection of 113 under which the deduction is claimed depends on various conditions such as whether the foreign corporation is a foreign affiliate as defined and the level of foreign tax paid.

3. Calculation of Deductible Amount:

- Assume the foreign country levied a tax of $200,000 CAD on the profit before Company F paid the dividend. Under subsection 113(1)(b), if that foreign tax qualifies as a "foreign accrual tax" (FAT), Company C can deduct the foreign tax amount in calculating its taxable income.

- Therefore, Company C would include the gross dividend of $1,000,000 CAD in its income but would also be able to deduct $200,000 CAD under subsection 113(1)(b).

- The net amount included in Company C's taxable income would be $800,000 CAD.

In practical terms, Section 113 helps avoid double taxation on income that has already been taxed in a foreign jurisdiction by allowing the Canadian recipient to deduct certain amounts from its taxable income.

Summary:

Section 113 ensures that Canadian corporations are not adversely taxed on the repatriation of foreign-earned profits by allowing them to deduct certain amounts, such as foreign taxes paid, when those earnings are brought back into Canada as dividends. This is particularly beneficial for multinational Canadian corporations with foreign operations.

- Section 138(6): Dividends from Insurance Corporations

This section applies to assessable dividends. Assessable dividends are dividends subject to Part IV tax, specifically to dividends received by insurance corporations. It allows insurance companies to deduct dividends received from shares they hold in other insurance corporations.

If you come across the term "assessable dividends" in relation to section 138(6), it's referring to the income from dividends that an insurance company must recognize and potentially can deduct under the specified conditions.

Example Scenario:

Let's say Life Insurance Company A holds shares in Life Insurance Company B. During the fiscal year, Company B pays a dividend to Company A. Under Section 138(6), Company A may be allowed to deduct that dividend from its taxable income, provided it meets the specific conditions and requirements set forth in this section.

This deduction prevents the double taxation of intercorporate dividends within the insurance industry, ensuring that the income is not taxed multiple times as it moves between related entities.

- In Summary:

These provisions ensure that dividends received under these categories may be deducted to avoid multiple layers of taxation.

- Section 112: Deals with intercorporate dividends within Canada.

- Section 113: Covers dividends from foreign affiliates of Canadian corporations.

- Section 138(6): Pertains specifically to dividends received by insurance corporations.

*Reference: CRA IT269R4 ARCHIVED - Part IV Tax on Taxable Dividends Received by a Private Corporation or a Subject Corporation

What is the RDTOH and how does it work?

What is the RDTOH and how does it work?

The RDTOH (Refundable Dividend Tax On Hand) is a mechanism in the Canadian tax system designed to achieve tax integration and prevent the deferral of tax on investment income by Canadian-controlled private corporations (CCPCs). It is used to track taxes that will be eligible for a refund on dividends. Here’s an explanation of how it works:

Purpose of RDTOH: The primary purpose of RDTOH is to ensure that the investment income earned by Canadian controlled private corporations and then distributed as dividends is taxed at a rate similar to the rate that would apply if the income were earned directly by an individual. It prevents corporations from indefinitely deferring tax on investment income by holding it within the corporate structure. It is not available to public companies; only CCPCs that pay part IV tax on dividends from passive income.

How RDTOH Works

1. Accumulation: When a CCPC earns certain types of income, such as interest, taxable capital gains, or dividends from non-connected corporations, it has to pay Part I or Part IV tax. A portion of these taxes is added to the corporation’s RDTOH account.

2. Tracking RDTOH: Corporations need to track two components of RDTOH:

- Eligible RDTOH: Relates to eligible dividends which qualify for the more favorable tax treatment.

- Non-eligible RDTOH: Relates to non-eligible dividends which don’t qualify for the favorable personal tax-treatment rates.

3a. Tax Calculation for an eligible RDTOH per section 129(4) of ITA:

- Eligible RDTOH opening balance

- - Eligible dividend refund from the prior year

- + Part IV tax paid on eligible dividends received

- Eligible RDTOH closing balance

3b. Tax Calculation for an non-eligible RDTOH per section 129(4) of ITA:

- Non-eligible RDTOH opening balance

- - Non-eligible dividend refund from the prior year

- + Refundable part I tax: the lessor of (i) 30 2/3% of aggregate investment income, or (ii) 30 2/3% x (taxable income - SBD), or (iii) Part I tax payable

- + Part IV tax paid on non-eligible dividends received

- Non-eligible RDTOH closing balance

4. Refundability: Canadian controlled private corporations can get a refund from their RDTOH account when it pays taxable dividends to its shareholders. Specifically, the refund is calculated as the lessor of: (i) $38.33 for every $100 of taxable dividends paid, or (ii) the RDTOH balance available for that type of dividend. This refund ensures that when corporations pay dividends, the tax burden is ultimately passed to the individual shareholders, maintaining tax neutrality.

Conclusion: RDTOH is a feature of the Canadian tax system that helps maintain fairness and tax neutrality. It ensures corporations do not gain an undue advantage by accumulating investment income and encourages the timely distribution of earnings for taxation at the shareholder level. You can find the RDTOH calculation and any dividend refund on page 7 of your T2 jacket.

What is the capital dividend account in Canadian controlled private corporations?

What is the capital dividend account in Canadian controlled private corporations?

The Capital Dividend Account (CDA) in Canada is a notional account used by Canadian controlled private corporations to track certain tax-free earnings that can be distributed as dividends to shareholders on a tax-free basis. These earnings generally arise from non-taxable capital gains and certain other tax-free transactions.

Key Items Found in and Affecting the CDA

1. Non-Taxable Portion of Capital Gains: When a corporation realizes a capital gain, typically only 50% of the gain is taxable. The non-taxable portion (the remaining 50%) is credited to the CDA.

2. Life Insurance Proceeds: Proceeds from life insurance policies received by the corporation upon the death of the insured person, minus the adjusted cost basis (ACB) of the policy, are added to the CDA.

3. Capital Dividends Received: Capital dividends received from other corporations are also added to the CDA.

4. Capital Loss Utilization: Reductions occur in the CDA when capital losses realized by the corporation offset previous capital gains.

5. Capital Dividends Paid: Payment of a capital dividend reduces the CDA balances.

Purpose of the CDA

The purpose of the Capital Dividend Account is to permit Canadian controlled private corporations to distribute certain types of earnings to shareholders tax-free. This helps avoid double taxation, where the same income might otherwise be taxed at both the corporate and personal levels.

Administration and Reporting

1. Form T2054: To declare a capital dividend, the corporation must file Form T2054, "Election for a Capital Dividend Under Subsection 83(2)," with the CRA. The form must be filed on or before the date the dividend is paid.

2. Maintaining Records: Accurate records must be kept to track the CDA balance accurately. This is crucial for compliance and to ensure that dividends do not exceed the available CDA balance. The easiest way to do this is use Schedule 89 found in your corporate tax return.

3. Confirming CDA Balance: It's advisable to confirm the CDA balance with the CRA before paying out a capital dividend to avoid any potential penalties or mistakes. You do this by filing a Schedule 89.

Benefits

1. Tax-Free Dividends: Shareholders (Canadian residents) receive dividends from the CDA tax-free, which can be a significant tax planning advantage.

2. Efficient Distribution: It allows for the efficient distribution of non-taxable portions of gains and tax-free life insurance proceeds to shareholders.

In summary, the CDA provides a mechanism for Canadian controlled private corporations to pass certain tax-free earnings to shareholders without additional tax burdens, thereby enhancing the overall tax efficiency for the corporation and its shareholders.

I want to pay a capital dividend. How do I do this? Where do you find your CDA (Capital Dividend Account) balance and how you confirm this balance with CRA?

I want to pay a capital dividend. How do I do this? Where do you find your CDA (Capital Dividend Account) balance and how you confirm this balance with CRA?

To confirm the balance in your Capital Dividend Account (CDA) with the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), follow these steps:

1. Review Internal Records: Verify your own records to ensure that the calculations and transactions contributing to the CDA balance have been accurately documented. You would normally find this information on Schedule 89 of your T2 return, not in your financial statements.

2. Request a CDA Balance Verification: File a Schedule 89 - Request for Capital Dividend Account Balance Verification. Confirming your CDA balance with the CRA before declaring and paying a capital dividend is crucial to ensure compliance and avoid significant (some would say severe) penalties associated with paying in excess of your CDA.

3. Filing an Election (T2054): If you are planning to pay a capital dividend, you need to file an election using Form T2054, "Election for a Capital Dividend Under Subsection 83(2)" on or before the date the dividend becomes payable or when any part of the dividend is paid.

- You file this form separately from your corporate tax return.

- When you file this form, the CRA will review your account and either confirm the balance or issue a notice of assessment or determination.

- You must include (1) a Schedule 89 which supports your CDA balance calculation; and (2) attach a certified copy of the capital dividend resolution as required by Regulation 2101.

- Part 8 - Late Filing Penalty must be completed on Form T2054 with payment attached if you paid your capital dividend and are filing the election after its due date instead of before.

4. My Business Account (or Represent a Client:) You can also access CRA's online portal "My Business Account" to view your account balances and transactions under the RC Corporate section. Ensure you or your authorized representative have set up access to your account.

By following these steps, Canadian controlled private corporations (CCPCs) should be able to accurately confirm their CDA balance with the CRA.

What is the difference between passive income and specified investment business income (SBI)?

What is the difference between passive income and specified investment business income (SBI)?

In the context of Canadian tax, particularly for Canadian Controlled Private Corporations (CCPCs), the terms "passive income" and "Specified Investment Business Income (SBI)" relate to different types of corporate income that have distinct tax treatments. Here are the differences between the two:

Passive Income

1. Definition: Passive income generally refers to income that is not earned from active business operations. Common examples include interest, dividends, rental income from real property, and royalties.

2. Tax Rate: Passive income earned by Canadian controlled private corporations is subject to a high rate of tax compared to active business income. This is because, under Part IV of the Income Tax Act, a refundable tax is levied on investment income.

3. Refundable Dividend Tax on Hand (RDTOH): A portion of the tax paid on passive income may be refunded when the corporation pays taxable dividends to its shareholders. The refundable tax is tracked in the corporation's RDTOH account.

4. Impact on Small Business Deduction (SBD): Passive income in excess of $50,000 can impact the CCPC’s ability to claim the SBD. Once passive income exceeds this threshold, there is a reduction in the corporation's SBD limit, leading to a higher tax rate on active business income.

Specified Investment Business Income (SBI)

1. Definition: SBI is a type of passive income earned by a business that principally derives its income from property, such as real estate, rentals, or investments. A business whose principal purpose is to earn income from property and that does not employ more than five full-time employees throughout the year is classified as a Specified Investment Business.

2. Active vs. Passive Distinction: While this income might seem passive, it is categorized separately because it comes from business activities specifically aimed at generating income from investments.

3. Tax Rate: SBI earned by Canadian controlled private corporations is also subject to high tax rates similar to other forms of passive income. It does not qualify for the small business deduction.

4. Number of Employees Condition: If the business has more than five full-time employees, it may qualify as an active business and not as a Specified Investment Business, which could then allow access to the lower active business income tax rates.

5. Excluded from Active Business Income: Income from a SBI does not qualify as active business income and, therefore, cannot take advantage of the lower corporate tax rate available to active business income eligible for the small business deduction.

Key Takeaway

- Passive Income includes various forms of non-operating revenue such as interest, dividends, and rentals, subject to high tax rates and potential refundable taxes under RDTOH.

- Specified Investment Business Income (SBI) is a subset of passive income earned by businesses focusing primarily on investment-type revenue, also generally subject to high tax rates but with specific conditions like the number of employees defining its classification.

What is the difference between specified corporate income (SCI) and specified investment business income (SBI)?

What is the difference between specified corporate income (SCI) and specified investment business income (SBI)?

SCI and SBI are different types of business income that can impact how income is taxed for corporations. It's important not to confuse the two.

Both specified corporate income and specified investment business income are terms that relate to the application of the small business deduction (SBD), which is a beneficial tax rate applied to the first $500,000 of active business income for Canadian-controlled private corporations (CCPCs). Here's a breakdown of these terms and their implications:

Specified Corporate Income (Anti-avoidance Rule)

SCI is primarily concerned with preventing fragmentation of a business's operations to claim the SBD multiple times improperly. This anti-avoidance rule is designed to address circumstances where a corporation provides services or property to another corporation with which it does not deal at arm’s length and the income derived is not considered active business income (ABI).

Key Features:

- The specified corporate income applies where a CCPC earns income from providing services or property to a non-arm's length entity that could have directly earned such income.

- This income is generally ineligible for the small business deduction unless both parties elect to have the income deemed active business income within certain prescribed limits.

Impact on Small Business Deduction:

- Without proper structuring, such income could be excluded from the SBD, impacting a CCPC's ability to benefit from the lower tax rates on small business income.

Specified Investment Business Income

SBI refers generally to income derived from a corporation that earns income primarily from property unless the corporation employs more than five full-time employees throughout the year or is otherwise actively engaged in business activities. Typical sources of specified investment business income include:

- Rent

- Interest

- Dividends

- Royalties

Impact on Small Business Deduction:

- A corporation that earns such income will not benefit from the small business deduction on this income because it is not considered active business income. This means it will be taxed at the higher general corporate tax rate unless the corporation meets the exceptions (more than five full-time employees or active engagement in business activities).

Key Takeaway

Both specified corporate income address and specified investment business income different aspects of income classification for tax purposes. Specified corporate income targets potential intra-group arrangements aimed at unfairly maximizing the SBD. Specified investment business income affects the active/passive income distinction and eligibility for the SBD based on the nature of the income. Understanding and managing these distinctions is important for tax planning to ensure a corporation optimizes its tax liabilities. As tax rules are complex and subject to changes, consulting with a tax professional is advised for guidance on these two different types of business income.

Is specified corporate income the same as income splitting or income sprinkling?

Is specified corporate income the same as income splitting or income sprinkling?

No, specified corporate income is not the same as income splitting or income sprinkling, although they are related in terms of tax planning and avoidance strategies.

Specified Corporate Income

Purpose: The specified corporate income rules are primarily an anti-avoidance measure targeting corporate income that might be inappropriately classified to claim the small business deduction. This rule prevents corporations from artificially splitting business operations to multiply access to lower tax rates on active business income via the small business deduction.

Application: It affects transactions or arrangements where income is passed between corporations under non-arm's length relationships to claim multiple deductions improperly.

Income Splitting (or Income Sprinkling)

Purpose: Income splitting, or income sprinkling, involves distributing income among family members (often through dividends), who might be in lower tax brackets, to reduce the overall tax burden. This strategy tries to take advantage of the progressive tax rate system.

Application: Typically, income splitting involves the use of family trusts, partnerships, or directly paying dividends to family members, such as children or spouses, to shift income.

Recent Tax Changes:

The Canadian government implemented rules in 2018 to address income splitting, notably through Tax on Split Income (TOSI) rules. These rules limit income sprinkling benefits, particularly for individuals aged 18 and over receiving income from a family business.

Key Differences

- Nature of Target: Specified corporate income targets inter-corporate transfers and deductions; income splitting targets distribution among individuals.

- Rules and Impact: Specified corporate income affects corporate tax rates through eligibility for the small business deduction. In contrast, income splitting involves personal tax rates and family tax planning.

Both strategies have been scrutinized by tax authorities given their potential for abuse, leading to ongoing evaluations and updates in tax legislation to prevent tax avoidance. These are complex tax issues. To ensure you are not offside the current tax laws, it is always prudent to chat with your accountant about how these issues affect you both from a business perspective and a personal perspective.